If you use a Kindle, odds are you’ve wished it was possible to fill it with all the books weighing down your shelves. Well, this autumn, that reality may be a step closer.

Amazon’s new Kindle MatchBook scheme offers a free or discounted digital copy of every book you’ve ever purchased from them, dating back to 1995 and covering 70,000 titles. It’s currently only available in the US, but if AutoRip (its sister scheme for music downloads) is anything to go by, MatchBook should be rolled out in the UK in six months or so.

A lot has been said about the conflict between print and digital media. The arrival of MatchBook could signal a new way of looking at the problem – why not make the best of both worlds?

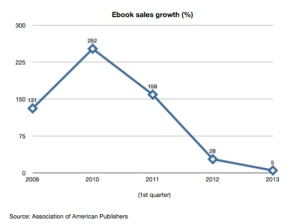

As well as encouraging shoppers to buy print books, MatchBook may also help ebook sales, which have levelled out over the past two years. Those reluctant to convert to a digital format may be persuaded by a good bargain, widening the market for ebooks while still supporting a physical format.

From a more cynical viewpoint, this could be seen as the start of Amazon’s attempt to phase out their print division by selling ebooks more aggressively. However, it’s unlikely that this will be successful any time soon. The physical book is not just words: it’s the feel of the pages, the weight of the covers, a tangible object. A large proportion of books are bought as gifts, too, and it’s much nicer to receive a lovingly-wrapped parcel than an online voucher.

Kindle MatchBook looks set to be a success. But the industry is still in a state of flux, and it’s still impossible to tell where we’ll end up. The concept of ‘creative destruction’ is one that has often been applied to the publishing industry. We are still finding new ways to function in the face of sweeping technological advances.

“A railroad through new country upsets all conditions of location, all cost calculations, all production functions within its radius of influence; and hardly any ‘ways of doing things’ which have been optimal before remain so afterwards.” Joseph Schumpeter, 1939